5 Lent: 9 March 2008

(Ezekiel 37:1-14/Psalm 130/Romans 8:6-11/John 11:1-45)

The Last Word

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. Amen.

Marley was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The register of his burial was signed by the clergyman, the clerk, the undertaker, and the chief mourner. Scrooge signed it: and Scrooge’s name was good upon ‘Change, for anything he chose to put his hand to. Old Marley was dead as a door nail.

This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful can come of the story I am going to relate.

-- Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol

I’ve stood beside too many graves, carried too many bodies in silent procession to them. If the Lord tarries, and I do as well, I will stand there again. If the Lord tarries and I do not, someone will stand there by my grave, someone will bear my body. We Christians try to put a good face on all this, of course, to bear witness to the hope within us, as well we should. Even at the grave we make our song: Alleluia, alleluia, alleluia (BCP 499). But, when the last Alleluia falls silent and we walk away, we know we have left something – someone, a part of us – behind. Though we make our song, in our bones we feel that death, at least for now, has the final word. And that word is silence.

So we understand Mary and Martha: their loss, their pain, their confusion at a friend who might have helped but chose not to. They are caught somewhere between reality and hope, where we all are at the grave: “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died,” said Martha, yet, “I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day.” On the last day, maybe – but in the meantime death has the final word.

Lazarus was dead, to begin with. There is no doubt whatever about that. The sisters knew it, the mourners knew it, the crowd knew it. The tomb had been sealed four days. Old Lazarus was dead as a door nail.

This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful can come of the story that John is going to relate.

The wonderful – wonder-filled – story of Lazarus doesn’t begin at the sealed tomb, or four days earlier when he died, or even two days before that when news reached Jesus of his friend’s illness. It begins in the mists of pre-history, in a garden. It was there God spoke to Adam, spoke words of provision and warning: ‘You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; 17but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die.’ But of course he did eat, he and the woman God had given him as companion. Then something quite unexpected happened, or rather didn’t happen. Adam didn’t die as God had warned. Not immediately, not on that day. Instead, Adam and Eve were exiled: from the Garden, from the tree of life, from the easy intimacy they had known with God and with one another. It is this exile which constitutes God’s faithfulness to his warning; it is this exile which constitutes Adam’s immediate death. Separated from the tree of life, from this life-sustaining sacrament of God’s grace, Adam spiraled downward into corruption, ending with his physical death: From dust he came and to dust he returned. It is no exaggeration to say that the harvest has begun the moment the seed has been planted. It is no exaggeration to say that Adam harvested the field of death the moment he planted the seed of disobedience. In the meantime, exile itself is seen as the immediate, visible sign of the death to come. In biblical literature exile and death are intimate companions, symbols one for another.

So it is that Ezekiel, writing in the 6th-century B.C., writing from exile in Babylon, envisions Israel as a valley of dry bones; Israel in exile is Israel as good as dead. The word of the Lord comes to Ezekiel, a word of resurrection, a word to end the exile.

“Prophesy to these bones, and say to them: O dry bones, hear the word of the LORD. Thus says the Lord GOD to these bones: I will cause breath to enter you, and you shall live. I will lay sinews on you, and will cause flesh to come upon you, and cover you with skin, and put breath in you, and you shall live; and you shall know that I am the LORD” (Eze 37:4-6, NRSV).

And because the word of the LORD has power to create what it speaks, no sooner had Ezekiel uttered the prophecy than “suddenly there was a noise, a rattling, and the bones came together, bone to its bone,” and sinews formed and skin, also. But the newly formed bodies were yet lifeless, without breath, without spirit.

“Prophesy to the breath, prophesy, mortal, and say to the breath: Thus says the Lord GOD: Come from the four winds, O breath, and breathe upon these slain, that they may live” (Eze 37:9, NRSV).

And Ezekiel spoke and the breath came and the bodies stood on their feet, a vast multitude. You see bones, I see an army, says the Lord God.

Thus says the Lord GOD: I am going to open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people; and I will bring you back to the land of Israel. And you shall know that I am the LORD, when I open your graves, and bring you up from your graves, O my people. I will put my spirit within you, and you shall live, and I will place you on your own soil; then you shall know that I, the LORD, have spoken and will act,” says the LORD (Eze 37:12b-14, NRSV).

Then something quite unexpected happened, or rather didn’t happen. Israel’s exile didn’t end. They did return home to rebuild Jerusalem and the temple. But the presence of God, the shekinah glory, did not return to inhabit the temple as in the days of Solomon. There were bones and sinews and skin all right, but no breath, no Spirit. Save for a few brief periods Israel was never again autonomous, never again sovereign. Pagans ruled the land: Syrians, Greeks, Romans. So it was that Israel remained in exile, dead and awaiting resurrection. So it was that death had the final word.

A notion developed in Israel to explain these unfulfilled promises and prophecies – a notion of the eschaton, the last days. One day, at the last day, Israel’s history would reach “ a great moment of climax, in which Israel herself would be saved from her enemies and through which the creator God, the covenant God, would at last bring his love and justice, his mercy and truth, to bear upon the whole world, bringing renewal and healing to all creation” (N. T. Wright, The Challenge of Jesus, p. 35). On this last day God himself would return to his kingdom, Israel. He would raise the righteous dead in a moment of national resurrection and the exile would end as the Spirit returned to the lifeless body of Israel. No longer would death have the last word.

“Now a certain man was ill, Lazarus of Bethany, the village of Mary and her sister Martha” (John 11:1): so begins the story of the raising of Lazarus. The sisters send an urgent message to Jesus who inexplicably – in their eyes and in the eyes of his disciples – delays until Lazarus dies. Only then does he make his way to Bethany.

When Jesus arrived, he found that Lazarus had already been in the tomb four days. Now Bethany was near Jerusalem, some two miles away, and many of the Jews had come to Martha and Mary to console them about their brother. When Martha heard that Jesus was coming, she went and met him, while Mary stayed at home. Martha said to Jesus, “Lord, if you had been here, my brother would not have died. But even now I know that God will give you whatever you ask of him.” Jesus said to her, “Your brother will rise again.” Martha said to him, “I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day” (John 11:17-24, NRSV).

And there it is – the hope of the eschaton, the hope of the last day. Martha knows that a great day is coming, a day when the Lord himself will return to deliver his people, to end the exile, to raise the righteous dead – the day Ezekiel saw in a vision and longed for. When the dead rise the exile will be over and God’s kingdom will come on earth as it is in heaven. In the meantime, death has the final word.

Jesus said to her, “I am the resurrection and the life. Those who believe in me, even though they die, will live, and everyone who lives and believes in me will never die. Do you believe this” (John 11:25-26, NRSV)?

With these words, amidst the tears and sorrow of a grieving family, Jesus proclaims the good news to Israel: the time has come, the last days have arrived, God is once again among his people, the breath of the Spirit is about to enter the lifeless body of Israel, and you will see the sign of this great and marvelous day of the Lord this very day, in this very place.

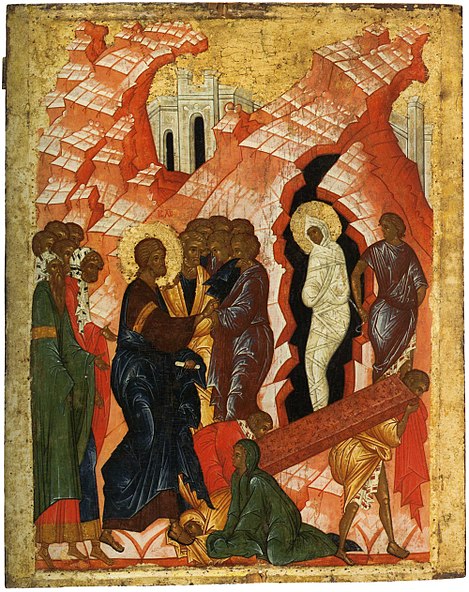

Jesus said, “Take away the stone.” Martha, the sister of the dead man, said to him, “Lord, already there is a stench because he has been dead four days.” Jesus said to her, “Did I not tell you that if you believed, you would see the glory of God?” So they took away the stone. And Jesus looked upward and said, “Father, I thank you for having heard me. I knew that you always hear me, but I have said this for the sake of the crowd standing here, so that they may believe that you sent me.” When he had said this, he cried out with a loud voice, “Lazarus, come out!” The dead man came out (John 11:39-44a, NRSV).

This is not just another in a long line of miracles. This is a sign: a sign that God has returned to his people in the person of Jesus of Nazareth, a sign that the last day is about to dawn, a sign that the exile is over, a sign that at last the justice and mercy and righteousness of God are now at work putting to rights all that is wrong in all of creation. This is a sign that soon and very soon, death will no longer have the final word, a sign that the final word will be the loud voice of Jesus crying, “Come out!” and we will come out.

The raising of Lazarus was Jesus’s great act of defiance in the face of the great enemy death – a challenge, a gauntlet thrown down. Death has been stalking Jesus, bringing him ever nearer Jerusalem, ever nearer Gethsemane, ever nearer Golgotha, ever nearer the cross – so death thinks. But all this time it is Jesus who has been luring death to its destruction. And with the raising of Lazarus Jesus humiliates death. Come death, do your worst. Come death who from Adam’s first sin has had the final word and hear the Lord himself cry, “Come out!”

And then something quite unexpected happened, or rather didn’t happen. Jesus didn’t defeat death. Not long after releasing Lazarus from death’s bondage, Jesus surrendered himself to death. Jesus died and like Lazarus was placed in a tomb and sealed there. The Jews had the last word: “Crucify him!” The Romans had the last word: “The King of the Jews.” Death had the last word: silence. And the exile continued and no Spirit entered the lifeless body of Israel. And all creation prayed with the sweet Psalmist of Israel,

I wait for the LORD, my soul waits, and in his word I hope;

my soul waits for the LORD

more than those who watch for the morning,

more than those who watch for the morning.

O Israel, hope in the LORD!

For with the LORD there is steadfast love,

and with him there is great power to redeem.

It is he who will redeem Israel from all its iniquities (Psalm 130:5-8, NRSV).

And on the third day, on the third day the final word was spoken: He is not here. He is risen as he said! Easter – the first day of the week – is the first day of the last days. The exile is over, God is among his people, new creation has dawned.

And then something quite unexpected happened, or rather didn’t happen. Rome didn’t crumble; Pilate just swept Jesus under the rug and went about business as usual. The Sanhedrin complimented themselves on a job well done – another heretic dispatched. The crowds who had followed Jesus dispersed. Nothing really changed. Sooner or later Lazarus died again and death pronounced the final word over him a second time. Or so it might seem.

But something quite unexpected had happened. In Jesus, God broke into the middle of history to inaugurate – to set in motion – that which Israel expected to see on the last day: the return of God; the end of exile; the establishment of God’s kingdom of righteousness, justice, and mercy; and the resurrection of the dead. And though it took time to understand it all, God did in and through and for Jesus – in the middle of history – what he will do for all creation on the last day. Jesus is the firstfruits of creation’s harvest to come. He is the power unto salvation and the sign of just what that means. Standing at the grave of Lazarus, his sisters were sure that death had the final word; and they were wrong. Standing at cross of Christ the Romans and the Jews and even Christ’s disciples were sure that death had the final word; and they were wrong. Standing at Auschwitz or Hiroshima or Rwanda or Darfur the world is sure that death has the final word; and they are wrong. Standing at the graves of mothers and fathers and sisters and brothers and husbands and wives and children we sometimes feel that death has the final word; and we are wrong. The final word was spoken to Lazarus: “Come forth.” The final word was spoken by the angel at the empty tomb: “He is not here. His is risen as he said.” The final word was spoken, is being spoken, and will be spoken over you, over all those in Christ Jesus.

If the Spirit of him who raised Jesus from the dead dwells in you, he who raised Christ from the dead will give life to your mortal bodies also through his Spirit that dwells in you (Rom 8:11, NRSV).

The exile is over; man has been reconciled to God through Christ Jesus. The dead have been raised to new life in the Spirit – now – and someday our mortal bodies will also be raised to new life. God’s kingdom has come in the midst of those who follow Jesus – imperfectly, yes, but here nonetheless; it has come, it is coming, it will yet come in all its fullness.

Death is still an enemy who will one day pronounce a word over us; we can’t deny that. Death will pronounce a word – just not the last word. That’s reserved for Jesus. Amen.